My First Smokey Skies

Thoughts on New York City's orange skies — and an exclusive interview related to my latest story for Atmos

LISTENING: to DCFC singing "nowhere left to go"

FEELING: heartbroken

SEEING: the orange sky pour into my office

“It feels like we’re living in a filter.”

That’s what my partner told me as we walked home from the laundromat Tuesday night. This week, New York City experienced some of the worst air quality in the world as particulate matter from wildfires burning in Canada made its way south.

It’s odd — to walk outside and feel as though you’ve hit an invisible wall, to feel the weight of the air around you, to feel a tickle in your throat with every inhale. And the smell. I fear it’ll be the smell of summers to come — a smell my children who do not yet exist will come to know well.

As I looked at the orange haze Wednesday, I couldn’t help but wonder: is this our future? Air quality alerts, red suns, and smog-laden skies are certainly one possibility. Will it be the one we choose?

Welcome to Possibilities, a creative climate newsletter that explores the possibilities that lie where crisis meets community. I’m Yessenia Funes, a journalist based in New York City who’s kinda freaking the fuck out.

Given the emissions already locked in, the Northeast is bound to see some level of wildfire-caused air pollution. Even the pollution from wildfires out West has made its way here in years past. However, the Northeast itself may see more wildfires due to climate change. I wrote about this in Atmos earlier this year. What happens when the fires burn closer to home? How bad will it be then?

Though this reality is possible, it’s not promised. We can still change course.

Wildfires happen for a multitude of reasons. A big contributor is people who unknowingly spark the fires — and, of course, rising temperatures from climate change that dry out forests, allowing such sparks to spread.

If our leaders stopped fossil fuel pollution, improved forest management (among individuals and officials), and developed policies that prioritized human health before crises emerged, these sorts of dark days wouldn't be so scary. We could find solace knowing the problem, at the very least, isn’t worsening. We would find comfort knowing that the most vulnerable — outdoor workers, the unhoused, elders, children — would be kept safe.

Ultimately, we need our forests alive, not turned to ash. Leaders need to act now to prevent more trees from burning and spewing pollution into the air.

If you're listening to the Death Cab for Cutie song above, there's one piece I really want you to listen to toward the end:

"He and I watch the foxglove grow through the clearcut / Where a forest once grew high and wild / For what is a funeral without flowers? / And ten thousand tombstones reaching for the sky."

I think they meant the trees when they described those tombstones. Something about that line haunts me every time I hear it.

Though Canadian forests deserve much more attention, I want to move on to a different forest: the Amazon.

This week, a story I wrote for Atmos's latest print issue finally published online: Talking Drums. This story looked at the manguaré, a set of drums the Bora people in the Peruvian Amazon use to communicate long-distance. It mimics their language, which is endangered, in a linguistically fascinating way. (Read the piece to understand more.) I loved working on this story even though I didn't get to visit the community in person.

My colleague Laura Beltrán Villamizar, however, did back in December. As the former photography director for Atmos, Laura traveled for over 18 hours on a boat to arrive at Brillo Nuevo, a Bora village deep in the rainforest where she joined photographer Florence Goupil. While Florence took the award-winning photos, Laura captured the soundscape you can listen to while reading the story online. Laura is now the editor-in-chief of Hermanas, a global ecosystem for women to build connections and share culture. Her experience visiting the Bora people was like nothing she had done before.

She shares her thoughts below in an exclusive interview with me. Starting in July, interviews like these will be for paid members only. Be sure to upgrade your membership if you don't want to miss out.

YESSENIA FUNES

What was the most challenging — and most rewarding — part of this reporting trip?

LAURA BELTRÁN VILLAMIZAR

The most challenging part was being in such a remote area. We didn't have control over resources. Eventually, we realized that there wasn't enough food for us. However, because of that, we were able to build a different level of relationship with the Bora community. We had to find ways to collaborate with them — like if you can find us a chicken, can we can all eat together? It was the only way to make it work. The challenge allowed us to connect with the community on a deeper level.

YESSENIA

Damn, that's so crazy. I would have literally died. I literally would have passed out from the hunger and stress. I don't think I can handle that.

LAURA

Yeah, it's full surrender to the situation. I told you before: we had to kill a turtle. They offered me thick white living worms, but I couldn't eat them. I told them to give me broth. And the beauty of it is that the only thing these people had to offer us was mambe, or coca powder, so we were all mambiando together. We're all surviving on coca powder because they had mountains of it. By the third day, we're crushing it in terms of work. It takes away your hunger. It gives you energy. This is how they thrive. It's like next-level green tea.

YESSENIA

That's wild. A big part of what you did there was capturing the audio. What compelled you to have that be a part of the story, as well?

LAURA

When you first presented the story to us, having a language enveloped in the shape of a drum was something that, for me, immediately needed to be captured not only through narrative and visuals — but also audio. If this is a disappearing language — the spoken one, but also the drums — how amazing would it be for us to record it and tell the story through audio? Yes, it is important to tell their story through photos, but I think the impact of the sound just elevated the reporting and the narrative.

YESSENIA

Was there a sound you didn't capture that you wish you had? Or a sound that has really stuck with you?

LAURA

The textures of the Amazon. The rest of the world has this idea of seasons: winter and spring, a time for sleeping and a time for harvesting. The Amazon does not stop. And you can hear that in the way the rain falls every single day, the way that the birds talk to each other constantly. It doesn't stop. It's a constant soundtrack of nature doing its work. And I felt that this is truly the lungs of the world. There is not a moment when the winter comes to the Amazon. And you can hear that.

YESSENIA

What was it like for you seeing Florence, the photographer, work?

LAURA

I had always wanted to work with her. She has been telling Indigenous stories in the Peruvian Amazon for many years. I knew that she had a sensitivity we needed to tell the story. And it was great to be with her so that we were not alone as women. And then for both of us to bounce back ideas: are there things we know we're both going to capture that we can play around with? Her photography would inspire me to record certain things. It was a great collaboration.

YESSENIA

Why was it important for you to find a photographer based in Peru for the story that had that experience covering Indigenous communities?

LAURA

It was crucial. There was a moment when we were wrapping up our work, and there was this expectation of payment. Her sensibility in understanding Indigenous communities and the Peruvian context in which these communities live, which is slightly different than the Colombian or the Brazilian, was crucial. Coming in as an outsider definitely has an impact on how you are seen by these communities. The way that she approached the project and the way we were able to support the community by paying them directly was crucial for us to keep a healthy relationship between storytellers and the community — and for the community to feel supported and heard and seen.

YESSENIA

What advice might you have for other storytellers who want to cover the Amazon and these remote communities?

LAURA

Be aware of the local politics. Self-awareness and research are crucial. Whose voices are you elevating? What are the community's expectations? Be very clear about expectations from the get-go. In terms of travel, who's your fixer? What's the situation at the border? On the way back from Brillo Nuevo, we had pirates hop on the boat, and then the captain scared them off with a rifle.

Be aware of what's happening and who you know. It can get really tense and really tricky really fast.

This interview has been lightly edited and condensed for clarity.

Currently Reading

My good friend Angely Mercado writes for Earther about Puerto Rico's extreme heat as Saharan dust arrives on the archipelago.

The case for cities setting up kids' college funds.

Why I'm forever in awe of science: scientists discovered a way to save some people suffering from psychosis.

What extreme heat means for Southeast Asian workers.

Now, I get why my friends who just became parents don't want anyone posting photos of their baby online. The Atlantic's got a good one here.

Yet another reminder of how the carceral state kills people.

From my homie Justine Calma: women environmental defenders need more protection.

Don't forget to listen to the podcast I hosted for re:arc institute. This is our final week of social promotion.

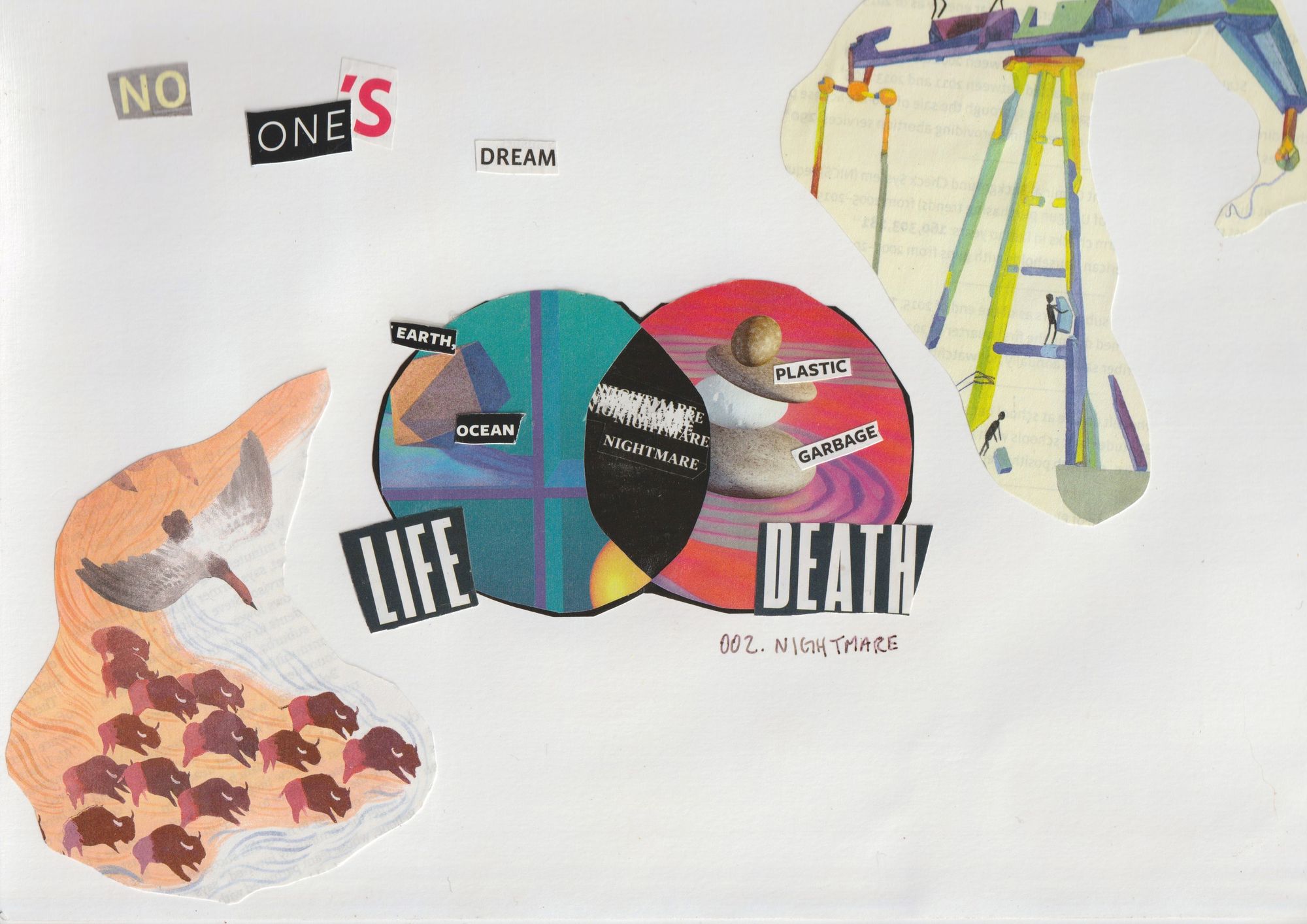

Collage

Where the Earth meets garbage,

a nightmare is born

Where the ocean meets plastic,

a nightmare appears

Where life and death meet,

there should not be so much darkness

This is no one's dream

Rest in Power

While we can't say for certain that climate change led to these specific weather events (we need an attribution study for that), we do know that the Earth's rising temperatures are already creating more disasters like these.

Flooding will be a common disaster here. In Turkey, rain-caused floods have killed at least two people who were swept away by the waters. In Algeria, a similar situation has claimed the lives of at least six.

In Haiti, a staggering 42 people have been reported dead after severe floods and landslides over the weekend. Thousands have been affected. Some 17 people were lost in southwestern China as floods and landslides claimed their lives.

Tropical Storm Mawar left its deadly mark as it made its way through Japan last week: at least two died.

See you next week. xx

- Yessenia