Let's Nerd Out

This edition is available to all (except the paid exclusives). Support my work and upgrade to paid here for as little as $5 a month.

LISTENING: to that "Wuthering Heights" soundtrack (yes, I loved it)

FEELING: busy with wedding prep!!!

SEEING: my 2-carat riiiing glisten, baby

Oil spills are devastating. Like life-changingly devastating.

For Tammy Gremillion of Lafitte, Louisiana, she believes the 2010 BP oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico was the beginning of the end for her daughter, Jennifer.

After the disaster, Jennifer joined a clean-up crew, as reported by the AP last year. She would leave work sites feeling unwell, covered in the stench of nothing good. Ten years after the spill, she died from leukemia, a cancer that can be caused by exposure to the chemicals in petroleum. Proving causation is a grueling task, but her mom, Tammy, is still fighting in the courts for justice.

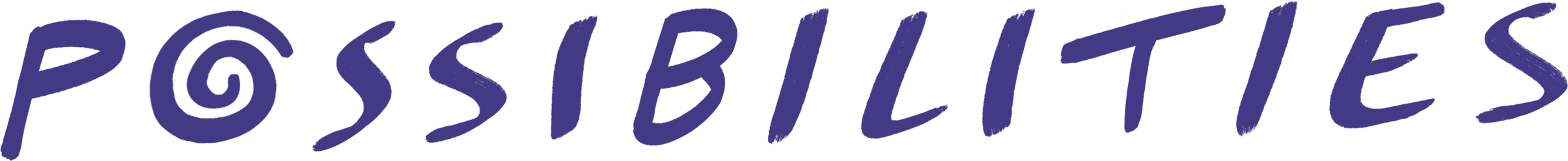

Though the BP oil spill remains one of the most widely known and studied, thousands happen every year — in U.S. waters alone. However, the world's water systems know no borders. Water moves regardless of whose jurisdiction it is in. And small-scale fishing communities suffer. Even without spills, offshore oil infrastructure takes fishing areas away from people who make a living (and their meals) on the water. Women, in particular, are vulnerable in countries like Ghana.

Offshore oil drilling is a dirty business — for the planet and the people who live nearby. It doesn't get much dirtier than an oil spill, though. And as long as rigs are built in the ocean, leaks and spills will keep happening.

What if scientists could devise a way to quickly clean up oil spills? But what if their approach looked straight out of a sci-fi film? Could we burn away an oil spill before the chemicals leach into the marine environment? Could a manmade fire tornado be a vision of our climate future?

Welcome to Possibilities, a creative climate newsletter on the possibilities that lie where crisis meets community. I’m Yessenia Funes, and I'm fascinated by the possibility of fire tornado science.

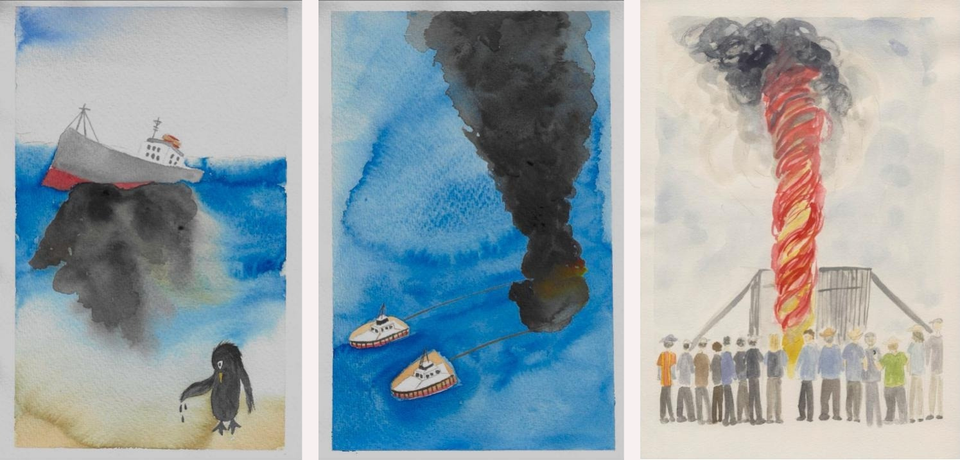

"We can actually use another truly destructive and very dangerous phenomenon for something beneficial," said Elaine Oran, a co-author on a paper about this idea who is a professor of aerospace engineering at Texas A&M University. "It’s a flip from the idea of 'how do we fight or kill it.'"

Fire tornadoes are typically associated with wildfires. They're literally what they sound like. If you still don't know what I'm talking about, check out the video below. Or watch the latest "Twisters" movie. (Seriously. I liked it!)

When I consider solutions to oil spills, my first thought is: Phase out the fossil fuel industry, duh. Until that happens, however, governments and first responders need tools that will protect marine ecosystems, as well as the health of workers and the local community. Unfortunately, there's no silver bullet when it comes to remediating tragedies like these. One approach may limit air pollution, but another may alter an ecosystem's microbial composition. Neither is great.

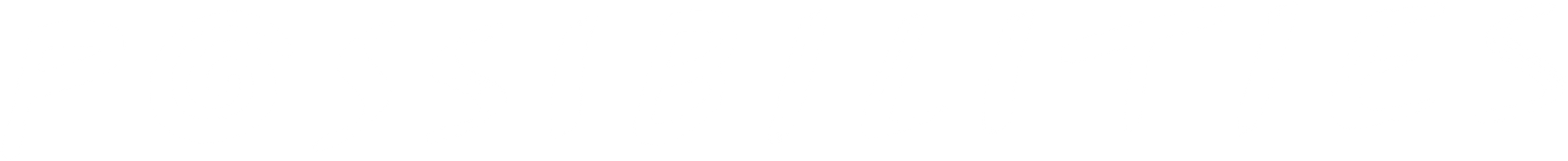

Currently, oil spill response can look a few ways. Crews can set up a sort of border to keep the chemicals from spreading and then use tools to remove as much oil as possible before using materials to absorb the oil. Some teams will light the oil on fire to burn it as quickly as possible. The main problem there is smoke and the subsequent toxic ash and sludge. Coastal communities already burdened by fossil fuels don't need another air pollution source to sicken them.

(I sent a few inquiries to researchers not involved in this project to hear their feedback, but I didn't receive a response in time. I'll share any points if they get back to me.)

Researchers estimate that burning an oil spill in a controlled fire whirl would reduce particulate matter emissions by 40 percent compared to the traditional approach. They came to this conclusion after creating a simulation between three 16-foot-tall walls placed together like a triangle. Their idea would likely only succeed in a real-life scenario where the wind and airflow were just right. To accomplish that, structures like the one in the experiment would need to be dropped directly onto an oil spill. That seems the best way to ensure safe conditions.

Oran shared in an email that her team thought of the idea after seeing videos of other fire whirls. One, in particular, stood out to them. After thousands of barrels of whiskey spilled into a Kentucky creek in 2003, footage revealed a fire tornado.

"We observed how the fire whirl was drawing the spilled fuel into it and growing," Oran explained via email. "We then looked at videos of in situ cleanup in the Gulf and noted that when a fire whirl happened to form spontaneously, the smoke turned from black to gray, which means it was a cleaner burn."

I only ever imagined fire tornadoes in the context of horrific wildfires. Now, I've got even more nightmare fuel. I appreciate the creativity researchers need to meet the reality of today's crises. I just wish we didn't have to prepare at all. 🌀

The newsletter ends here for free subscribers. Why not upgrade?